Hobbits, amirite?

When they’re not avoiding anything that makes them late for dinner, they’re pilfering ancient artifacts, accepting age-ending quests, sticking with their friends through thick and thin to the bitter end, testing the patience of wizards, getting kidnapped by Orcs, befriending tree-shepherding giants, sitting on the edge of ruin while discussing the pleasures of the table, swearing their service to kings, stabbing smack-talking lords of carrion and voracious giant spiders…and even carrying their masters up the faces of active volcanoes. Hobbits are, when it comes down to it, just a bunch of irrepressible lads and lasses going off into the Blue for mad adventures.

And a lot of people are very fond of them. Accordingly, on September 22nd, the in-world birthday of both Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, we celebrate Hobbit Day. It’s Tolkien Week, in fact, which has been a thing since 1978. Far too short a time.

Now, this is not really an essay, just an opportunity to share my own fondness for the species that gave J.R.R. Tolkien’s first book its title and when on to become a foundation to the snappy sequel that followed.

Well, okay, maybe also a very short look at their past. So just where are Hobbits in the big picture?

Those who explore The Silmarillion and the extended legendarium learn that Arda—that is, the entire world, of which Middle-earth is but a continent—was made for the Children of Ilúvatar. Ilúvatar is essentially God in Arda and the Children are both Men and Elves. This is their habitat, for different lengths of time. Dwarves were shoehorned into this two-race scheme when one of the Powers that preside over the world fashioned them (without permission) but then got conditional approval for them to stay around. Ents and Eagles…let’s call them special projects of the aforementioned Powers. Then you’ve got Orcs, trolls, dragons, and other monsters, all of which stem from various R&D projects under the management of the first Dark Lord, made in mockery of those above with the goal of destruction.

Okay, so where are Hobbits in all this? Tolkien famously didn’t tie everything up neatly in his secondary fantasy world by the time of his death—allowing all of us, I suppose, to talk and debate the matter. I think most would conclude that Hobbits are connected to Men and therefore share in their long-term fate: they live for a relatively short span of time (compared to Dwarves and certainly to Elves) before passing beyond the Circles of the World. Which means they’re more like us than any other fantasy race.

In “Concerning Hobbits,” the prologue of The Lord of the Rings, we’re told…

The beginning of Hobbits lies far back in the Elder Days that are now lost and forgotten. Only the Elves still preserve any records of that vanished time, and their traditions are concerned almost entirely with their own history, in which Men appear seldom and Hobbits are not mentioned at all. Yet it is clear that Hobbits had, in fact, lived quietly in Middle-earth for many long years before other folk became even aware of them.

No kidding. Two long ages go by without any mention of Hobbits. If they developed from the family tree of Men, we’re not privy to the specifics. In this way they may be like the Woses, the Wild Men of the Woods, who are certainly human but time or happenstance have given them different physical characteristics. Anyway, it’s not until the year 1050 of the Third Age—note, well after Sauron’s loss of the One Ring—that anyone even wrote an account of the Hobbits’ existence, though Elves, Men, and Dwarves each kept track of their own triumphs and disasters.

Buy the Book

Hollow Empire

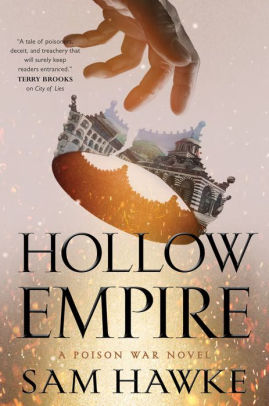

And even then, it was only upon the coming of the some Hobbits into Eriador that some noticed and thought to put pen to paper. These were their Wandering Days, their slow migration from the “upper vales of the Anduin, between the eaves of Greenwood the Great and the Misty Mountains.” There were the three basic branches of Hobbit-kind: the river-loving Stoors, the artsy and Elf-friendly Fallohides, and the hill-dwelling Harfoots. Interestingly, we’re told that it was due to the increase in the numbers of Men near them “and of a shadow that fell on the forest” (i.e. Sauron as the Necromancer settling into Dol Guldur) that prompted them to migrate westward.

The agrarian Hobbits eventually settled in some little-used lands in the wide Dúnedain kingdom of Arthedain. In the wars against Angmar and its ruler, the freakin’ Witch-king himself, we’re told that Hobbits contributed some archers once, “or so they maintained, though no tales of Men record it.” So they were there for a thousand years, minding their own business and never doing anything unexpected. Yet when old Witchy and his eight fellow riders go hunting for someone called “Baggins” in a placed called “the Shire,” well, it takes them a while. They’ve never heard of the place. They had to ask around, after all. Nevermind the fact that they once terrorized Eriador and ran roughshod over folks in the region for their boss.

So yeah, without even trying, Hobbits keep a low profile.

And when they actually try to stay hidden, they do a pretty good job of it. Bilbo might have famously botched his first burglar job, but that’s what being 1st level is like for any adventurer. He got better. And of course, the magic item he pocketed later helped in the stealth department. But Hobbits are naturally unobtrusive. Inconspicuous.

They possess from the first the art of disappearing swiftly and silently, when large folk whom they do not wish to meet come blundering by; and this art they have developed until to Men it may seem magical.

Almost as if by design, or by chance—if chance you call it. But it’s also a social trait, at least outside of the Shire and Bree-land where Hobbits are little more than a rumor. Denethor is amused by Pippin in Minas Tirith, but is hardly impressed. Théoden is genuinely appreciative of Merry but dismisses the idea of him riding to war.

‘And in such a battle as we think to make on the fields of Gondor what would you do, Master Meriadoc, sword-thain though you be, and greater of heart than of stature?’

Merry goes to war, anyway, with Éowyn’s help. And he suffers for his valor, yet he is overlooked in the ruin. While the bodies of the living and the dead are carried from the Pelennor Fields, Merry basically limps himself up into the city, stricken by the Black Breath, where it takes another Hobbit to notice him and steer him to the Houses of Healing.

Hobbits are tough as hell. “Concerning Hobbits” also informs us:

They were, if it came to it, difficult to daunt or kill; and they were, perhaps, so unwearyingly fond of good things not least because they could, when put to it, do without them, and could survive rough handling by grief, foe, or weather in a way that astonished those who did not know them well and looked no further than their bellies and their well-fed faces.”

Here is the great irony. Hobbits are beneath the notice of so many, right? We see it with the good guys and the bad guys alike. The Elves in Lothlórien know of them, but thought them long gone from Middle-earth (say, was Galadriel keeping her people in the dark about them?). To the Men of Rohan and Gondor they are halflings, “little people in old songs and children’s tales.” The three trolls don’t know what Bilbo is. Smaug’s never smelled one before. The Ringwraiths are sent to discover them because they’re an unknown quantity to their master. Sauron overlooks Hobbits big time, to his own uttermost ruin. Even Saruman, who at least knew about the Shire for far longer than his secret rival in Mordor, couldn’t be bothered with them until it was too late.

YET…

Yet we, Tolkien’s readers, find Hobbits anything but inconspicuous. They are the story. They are our eyes on the wonders and terrors of Middle-earth outside their borders. And almost every fan’s got their favorite Hobbit. I always want to default to Sam—of course I do: heroic, stubborn, loyal Master Samwise with all his folk wisdom and surprising spikes of empathy—but on some days it’s Merry or Pippin or even Frodo who takes the cake.

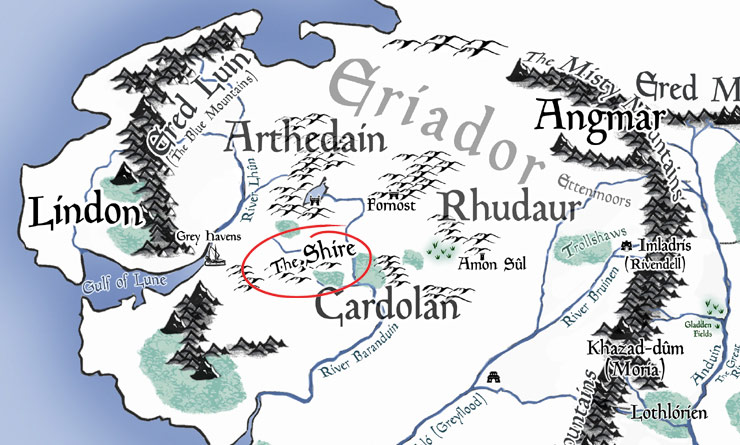

And Bilbo? Come on! And some part of me wishes the Tolkien Estate could hurry up and unearth The Lost Adventures of Belladonna Took and publish it already. And even Lobelia Sackville-Baggins has an entertaining character arc. And I always wish we knew more about Rosie Cotton. I wish Sam talked about her more throughout the dangerous quest to Mount Doom (but then that wouldn’t be like him, would it, as he is always sensibly concerned with Frodo’s well-being and their mutual survival?). At least Sam gets the ending he deserves.

For us, Hobbits don’t go unnoticed. For all that I love Tolkien’s most famous book, if you strip away Hobbits you’ve got a very different story that would still be beautiful and lofty—but it would be bereft of its heart. It would be less memorable. After all, everybody knows that Thorin Oakenshield speaks the truth when he says…

‘If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world.’

This is a given, right?

But oh, I mustn’t leave out mention of one particular fellow that it’s easy to forget is (or was) something like a Hobbit himself. As Gandalf explains…

‘I guess they were of hobbit-kind; akin to the fathers of the fathers of the Stoors, for they loved the River, and often swam in it, or made little boats of reeds. There was among them a family of high repute, for it was large and wealthier than most, and it was ruled by a grandmother of the folk, stern and wise in old lore, such as they had. The most inquisitive and curious-minded of that family was called Sméagol.’

It doesn’t seem fair to leave Sméagol entirely out of the discussion, since it was his greed—and his single-minded obsession with the Precious—which drastically altered the course of history in Middle-earth. Twice in particular: when he first acquired it and when he regained it.

And he endured for so long—living for hundreds of years, with the Ring’s help—by remaining unnoticed. How Hobbitish of him. While Frodo, Sam, Pippin, and Merry are often overlooked by bigger folk for their simplicity or even their resemblance (at a glance) to children, for Gollum it was usually pity or revulsion that stayed the killing blow. Of course, Gollum’s role in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings is incredibly nuanced, and worthy of its own explorations. But I wanted to keep his name in the air, this week. He deserves some acknowledgment.

So who is your favorite Hobbit and why? I’d like to hear!

And, outside of the books, are you a fan of any particular adaptations? In audio form, radio, film, TV, or illustration? I’ve talked about Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy before—here and here—largely in defense of them. I enjoy them, despite their many flaws, but I’m still glad of their existence. But I am especially fond of the Rankin/Bass version of The Hobbit as it was one my first exposures to the story. But what else do you recommend?

And what about the books? Any stories you could share about their discovery with friends or with your kids?

I’ll close with one of my own. When I traveled overseas with my family to Venice two years ago, I made a point to look for bookstores. I desperately wanted to see what Tolkien looked like in Italian. I wasn’t disappointed. While I couldn’t properly scour the city, I did find a couple of books. One store, Giunti al Punto (Come to the Point) had what I sought, along with some notable Tor titles…

So after flipping through Il Silmarillion and Beren e Lúthien, I purchased a lovely copy of Lo Hobbit, one illustrated by Alan Lee. When you know a book so well and know some of its passages by heart, it’s fun to recognize them even in a language you don’t speak. So while I can’t rightly read the story of how Bilbo Baggins, son of Belladonna Tuc, traveled with los nanos to La Montagna Solitaria to reclaim the treasure stolen by il drago Smaug, I know what’s going on.

Yet it’s The Hobbit illustrated by Jemima Catlin that I first read to my son when he was five. The art is endearing, and it makes the book seem smaller, more palatable to a little kid.

Also, what about costumes? Cosplay for conventions or moots or film parties? Or for Halloween? Let’s see your best hobbit impressions, if you’ve got them!

Happy Hobbit Day and Tolkien Week!

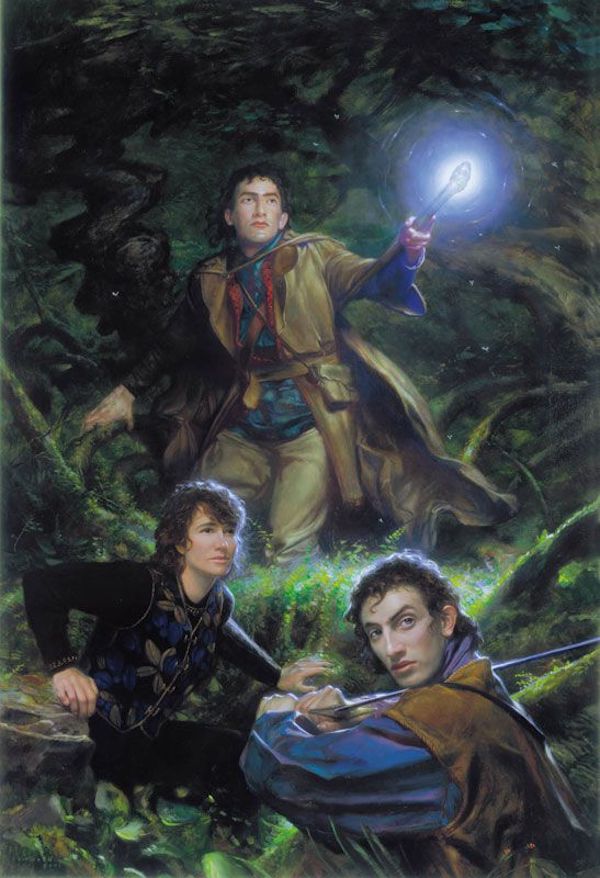

Top image from “Then There Were Three” by Donato Giancola.

Jeff LaSala can’t leave Middle-earth well enough alone, as evidenced by his Silmarillion Primer and now Deep Delvings articles. Tolkien geekdom aside, Jeff wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and now works for Tor Books. He sometimes flits about on Twitter.

I am a Merry fan. Book-version; the films relegated him too much to comic-relief. Merry is the party leader; he is the founder of the conspiracy of Frodo’s friends, the best informed as to where they should go and what they should do. As well as a master of herblore. He is just as loyal as Samwise is to Frodo. His loyalty to those whom he values is unmatched; it returns in his oath of fealty and desire to provide service to Theoden. But I have always felt he did all this not out of a sense of destiny, but because he’ll be damned if his friends face theirs alone. And it is the right thing to do. Of all the hobbits, he is the most akin to Aragorn (and thus suffers from the same’s lack of character growth: they are already grown, after all, so not much more to do).in understanding, preparing for, and committing to do what is necessary.

Don’t have a favorite, but am intrigued by what little we know of Bandobras “Bullroarer” Took. Some intrepid fan fictioneer ought to flesh out his story for us, if they haven’t already.

The first image of the article is not actually a picture of hobbits. It’s the cover of Diana Wynne Jones’ Hexwood. Which is awesome, but not so relevant to Hobbit Week.

@3: Perhaps that was used as a temporary promotional cover for Hexwood or something? (I can see that book’s had many different covers.)

In any case, I trust the artist‘s own words regarding the painting, from his art book Middle-earth: Journeys in Myth and Legend:

My question for the experts is did Tolkien create the hobbits long before he used them as friendly entry level characters for stories he told his small children?

Samwise is my favorite for the sheer awesomeness of his bravery, humility, and loyalty which was so great he was not corrupted by the Ring.

@@.-@ “Perhaps that was used as a temporary promotional cover for Hexwood or something?”

It’s the American 2002 reprint of Hexwood. Probably Donato originally painted it as a picture of hobbits then sold it to the publisher as a cover.

RE: Hexwood

Is there one character with a magic staff? Because none of the Hobbits had one.

@@@@@ 5- My nonexpert understanding is that hobbits are narratively native to the Hobbit, which was not, at the moment of its conception, immediately linked with the greater Legendarium, so I believe no.

@@@@@7- Ah, but the text given says that these are not the canonical hobbits that we know from The Hobbit or Lord of the Rings, but some projected adventurous Brandybuck ancestors, and who knows what kind of glowing sticks they might have found in their day?

My first introduction to The Hobbit was when I was 9 or so, after I’d finished the Narnia books. Christmas when I was 12 I got a first edition hardcover of The Silmarillion having already gone through Lord of the Rings a couple of times

I’m a Merry fan too and although the movie version was okay, he wasn’t much like I think Merry ought to be. I’m also celebrating my 46th wedding anniversary today, Sept. 22 — and yes, I picked that date on purpose. (My own son asked me about it the other day and when I said yes, he called me a nerd. Ah, the joys of parenthood — but he loves Tolkien as much as I do.)

@@.-@ The Hexwood thing is so absolutely bizarre I had to comment. I love Hexwood and that cover clearly depicts specific characters in the book. Honestly, it’s one of the better fantasy book covers from that time period in this respect. The brown coat Mordion’s wearing, Anne’s curly hair, Hume’s sword, it’s all there. Maybe Giancola later decided to portray this as a picture of hobbits rather than vice versa… which is just super weird! Sorry to derail I’m just astonished. But anyway, thank you for a great article!

I too have wondered at the ultimate origin of Hobbits in the scheme of Arda ever since I learned more about the legendarium.

It would be like Tolkien to leave that particular thread untied (witness Tom Bombadil), but the existence of the the Druedain or Woses, when I came to think about it, suggested to me that like them, they started as a tribe or tribes of Men who in isolation bred true for diminutive size, hardiness, and the other typical Hobbit characteristics.

So, when they came back into prolonged contact with Men, they (and Men) thought of themselves as a separate race and have no memory of having been a branch on the tree of Mankind.

As a branch of Men, they’d be among the Children of Iluvatar, and would have the same fate.

#12- Yes, if they had enough time to evolve in the Second Age it would make sense- small size, living underground, ability to move quietly, “the art of disappearing swiftly and silently when large folk whom they do not wish to meet come blundering by” would serve them by concealment; propensity to gorge when food was available, yet endure lean periods, would tie in with them emerging in troubled times- even their rock-throwing abilities would enable them to opportunistically snag small birds and animals.

#10- Join you in nerdhood; I chose September 22nd, 1972 as the day I first left Canada for Britain at the age of 18- three years later after Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia I made it back again.

It would be like Tolkien to leave that particular thread untied (witness Tom Bombadil), but the existence of the the Druedain or Woses, when I came to think about it, suggested to me that like them, they started as a tribe or tribes of Men who in isolation bred true for diminutive size, hardiness, and the other typical Hobbit characteristics.

Ah, but everyone recognises that the Woses are Men. They’re just unusual-looking Men. No one classes Hobbits as a kind of Men. Treebeard and his fellow Ents add them to the Lore of Living Creatures on their own line:

…presumably they change the second line from “four” to “five” too. But they are pretty sure that there’s a category called Men which includes everyone from Rohirrim to Numenoreans to Haradrim to Woses, and Hobbits ain’t in it. And Treebeard is very old and wise.

Now, Middle Earth is a creationist world. Different species are created different. That Elves and Men can interbreed and produce fertile offspring would make them the same species on our world, but it emphatically does not in Middle Earth. Evolution does not happen in Middle Earth!

So if Hobbits are a separate species, they were created separately. When? And by whom?

I think the answer to the first question is “late”. The Elves were woken first; then the Dwarves and the Ents; then the Men (at the start of the First Age). But there’s no record at all of the Hobbits before mid-Third Age.

And it’s canon that, while creation is a power that only Eru and a few other very powerful Valar (Aule, Yavanna) possess, less powerful entities like Maiar can take an existing species and change it a bit. Changing Elves into Orcs takes Morgoth’s power level, true – but that’s a fairly massive change. Something lesser, like changing Trolls into Olog-hai or Orcs into Uruk-hai, is within the power of a Maia like Sauron or Saruman.

So, a fairly powerful Maia could theoretically take the stock of Men and use it to create Hobbits – who are, as you say, much like Men, but smaller, less ambitious, less hungry for power (and so more resistant to the lure of the Ring), and keener on the simple pleasures of life.

The Istari, the Wizards, are powerful Maia. They arrive in Middle Earth in the year 1000 of the Third Age – before the first recorded sightings of Hobbits, but not that long before.

And one Wizard in particular has always devoted a lot of time and attention to the Shire and its residents. One might even characterise his interest as paternal…

@1 and @10, votes for Merry! (Not that we’re voting.) Yeah, Merry is an easy sell, and yes, nearly as mature as Frodo (and becomes at least his match as time goes by). He does so many good things, but his partnership with Éowyn is the sweet spot to me. Both come from such different worlds but in that moment of time become restrained and frustrated in the same ways, forming such a remarkable relationship.

Regarding the illustration “Then There Were Three,” I’ve asked Donato himself about it. Maybe he’ll weigh in.

@14, I wouldn’t say evolution doesn’t exist in Middle-earth. I think the concept is there, and applicable, but it plays out differently. It’s just not characterized in the same way as it is for us. Consider the Avari, the Unwilling, the Elves who didn’t even begin to follow Oromë on the great journey to Valinor. They are the Dark Elves, the Moriquendi, and physically/spiritually it’s implied that they’re a bit different from the Eldar, those who made it to Valinor and became the Calaquendi and even from those who remained on Middle-earth and also are considered Dark Elves for not having seen the Two Trees. Is that evolution? Not…exactly? But Men splinter and take on different physical characteristics: the Lossoth, the Drúedain, the Easterlings, the Southrons, the Dunlendings, the Woses; how did those distinctions come about if not by evolution based on region? I don’t think each group of Men forking off in a new direction was followed by a Maia who worked to alter them as time progressed.

As for Treebeard, yeah, he’s very old and very wise, but even Tolkien second guesses him for us. He doesn’t hold that all his ancient characters have all the facts. Even Gandalf is mistaken sometimes (like when he says at the Council that the Ringwraiths have their rings; it’s said elsewhere that Sauron keeps them). In his draft letter to Peter Hastings (Letter 153), from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien), Tolkien wrote:

That was on the topic of the nature of Orcs (which I intend to write about soon), but the point is that Tolkien makes his characters fallible so I wouldn’t hold everything Treebeard says as truth. His classification of the races and of Hobbits is endearing and wonderful, but I don’t think an accurate roster for Middle-earth.

In the HoMe books, when Tolkien refers to the final fate of Frodo (after departing from the Grey Havens), his fate sure sounds like the fate of Men.

But Men splinter and take on different physical characteristics: the Lossoth, the Drúedain, the Easterlings, the Southrons, the Dunlendings, the Woses; how did those distinctions come about if not by evolution based on region?

In some cases it was environmental; the Numenoreans lived geographically close to Valinor and so became “nobler” in the sense of taller and longer-lived, their relatives back in Middle Earth were smaller and shorter-lived. Similarly, the Calaquendi lived in Valinor itself, in the light of the Trees – surely that had a physical effect on them compared to their relatives in the darkness of Middle Earth.

But for the rest, why not assume that they were born that way, or rather created that way – that when the first Men awoke in Hildorien, some of them were black-skinned, some pale-skinned and so on?

I don’t see why even a ‘created’ world couldn’t then have evolution later on; perhaps that would just be part of the song.

The comments on the cover/iimage are cracking me up – I have to admit, the hobbit in the floral vest doesn’t so much remind me as a hobbit, but as a woman from the 80s rocking a perm. Even the proportions don’t really seem hobbit-ish to me. (Although – looking at the description, it seems like it isn’t actually intended to be Lord of the Rings characters, so maybe it IS a female hobbit).

The proportions are a bit more humanish than we usually see, but if you look at Donatao Giancola’s other works, this seems to be his preference for Hobbits. I don’t recall that Tolkien addresses proportions, just approximate heights, etc. Certainly these three are leaner than most, but I think it’s in keeping with his style. Compare a side by side with a taller figure:

I don’t see why even a ‘created’ world couldn’t then have evolution later on; perhaps that would just be part of the song.

The main reason is that there hasn’t been time. Humans awoke at the dawn of the First Age, only 7000 years before the events of “The Hobbit”. Not enough time for speciation, certainly not of a slow-breeding species like humans. Not enough time even for much differentiation in terms of phenotype; the San bush people of southern Africa are far less different from their neighbours than Hobbits from Men (they’re shorter and have a few other minor physiological differences), and it’s thought that the split there happened about 100,000 years ago. Native Americans split from their Asian ancestors about 12000 BP and the differences there are basically cosmetic.

I’m team Samwise all day every day (and in the films also Team Pippin, because Billy Boyd). Sam’s the hero of the book, and I will die on that hill!

Quote from one of the two “in defense of The Hobbit films” articles cited above: “Now I, too, was wistful when I heard that Guillermo del Toro wasn’t going to direct as originally intended”

Honey, I wasn’t wistful. I was homicidal. Jackson accomplished a few nice things – and tainted the whole with his juvenile humor (fart jokes in Tolkien – yeah, thanks, Peter) and inability to keep from “fixing” aspects of the story. I loathe that man.

@3 @@.-@ Sometimes art gets reused in strange ways. The cover art on my copy of the Silmarillion (from Darrell Sweet) also showed up as the cover for one of Marion Zimmer Bradley’s books (I don’t remember which one).

I did not understand Sam. I totally took his loyalty and devotion to Frodo for granted. I outright resented it when Shelob captured Frodo and then Sam took the Ring, briefly becoming the protagonist of the story. I then thoroughly resented him when Tolkien chose to end the story only halfway through the final volume, with a simple “Well, I’m back.”

It wasn’t until after many years and many readings that I grew up and read some commentary (probably on this site) in which people expressed admiration and appreciation of Sam. Once I read the explanations and became better acquainted with the professor’s own background and intent, I was amazed! The humble servant become side-kick was really the hero of the story!

@14, my husband has been nittering away for years on a fanfic where, in a world with no hobbits, Gandalf takes the ring and goes bad in Gandalfian ways – using his power to make the world good exactly according to his liking, eventually becoming a cruel tyrant – and humans become a hunted race who eventually diminish in stature. Radagast, who has hid out from Gandalf all these years, finds a few of these diminished humans and sends them back in time, where they become the ancestors of the hobbits.

My favorite?

She resisted the temptation to take the Ring when it was within her grasp (instead filling her umbrella with other small objects), endured tragic loss, and was eventually released from bondage and allowed to return home.

Lobelia (the Galadriel of Hobbits) for the win!

Are those hobbits in the first illustration?

They all have long faces with aquiline features, and look more like elves or men to me –not to mention the magic staff?

Fanfic suggestion: Tales of Grubb, Grubb, and Burrows, the firm that attempted to auction off Bag End and its contents a the end of The Hobbit. After Sharkey met his end, there would have been a huge number of lawsuits in and around the Shire.

@@.-@ @6 @22 …wouldn’t be the only repurposed Ginacola art. I saw an exhibit of his once with a painting of Gandalf on Shadowfax, which I later realized was also the cover of Banewreaker by Jacqueline Carey. I wish I had thought to ask him the story behind that.

Marry and Pippin! No one mentioned second breakfast! Personally I thought that was the best quote, loved Merry and Pipins horror and incredulity at not getting it while on the road, and have second breakfasts (and the rest of the six meals) myself most days!

The first image by Donato is certainly a cover for Hexwood by Diana Wynne Jones. I’ve got the book in front of me! Those characters are by no doubt Mordion, Ann, and Hume from top down. Strange Donato would say they’re Hobbits especially since covers are usually commissioned by publishers, no?

On another note, Diana Wynne Jones has a lovely essay about Lord of the Rings and Tolkien perfecting narrative. Some of you might find it interesting to read!

@24, SaintTherese has he published it online at all? Because I really want to read that fic!

@31 Sadly, no.

You’re all forgetting the other hobbit friend in the conspiracy, who bore his fair part in the story: Fatty Bolger. The Faithful Sidekicks have a song about him: https://thefaithfulsidekicks.bandcamp.com/track/fatty-bolger

Also, over on the Virtual Filksing [legal-to-download mp3s organized by topic], Leslie Fish’s first filksong, “Fellowship Going South”: http://www.prometheus-music.com/virtual.html

@33 Fatty Bolger, good call.

And thanks for the share! Gosh, I’m not really into filk music, but I do like some songs here and there. And I see this “Fellowship Going South” is performed by Julie Ecklar, who I only ever knew from her Elfquest music. (I wasn’t even big into Elfquest as a kid, but I did like that album!)

@27 Hywel,

Grubbs, Grubbs, Burrows, and Grubbs are in fact defending Frodo and Bilbo in the matter of Smeagol, Tauriel, and Estate of Smaug v Bagginses.

@30 re: commissioned covers

I read a lot, A LOT, of SF&F in the 70s and 80s. I still read a lot but back then I’d sometimes read a book a day (admittedly they were shorter). For many of them, though not all, the covers obviously had absolutely nothing to do with the books. A cover might show space ships near a planet but the story not involve spaceships at all. I vaguely remember reading somewhere that publishers would buy up artwork and just slap it on the next book to come along. “Big name” authors seemed to get covers specifically targeted for their books.